Water and air do not adhere to lines drawn on a map. Plants and animals do not respect man-made boundaries, and often require much larger areas than we allow. As climate change continues to alter the behavior of wildlife and the function of ecosystems, connectivity also preserves avenues for longer-term northward migration of species. To stay healthy, landscapes require interconnection.

Recognition of this fact has led to the rise of so-called “landscape-scale” conservation, which seeks to prioritize large-scale connectivity across jurisdictional boundaries, including pollution reduction and mitigation, safe passage for wildlife across roads and fences, and healthy riparian (streamside) habitats for fish, birds, and insect pollinators. Such efforts are already underway in North America, including the well-known Yellowstone to Yukon corridor in the Rocky Mountains and the Algonquin to Adirondacks corridor in the temperate northeast.

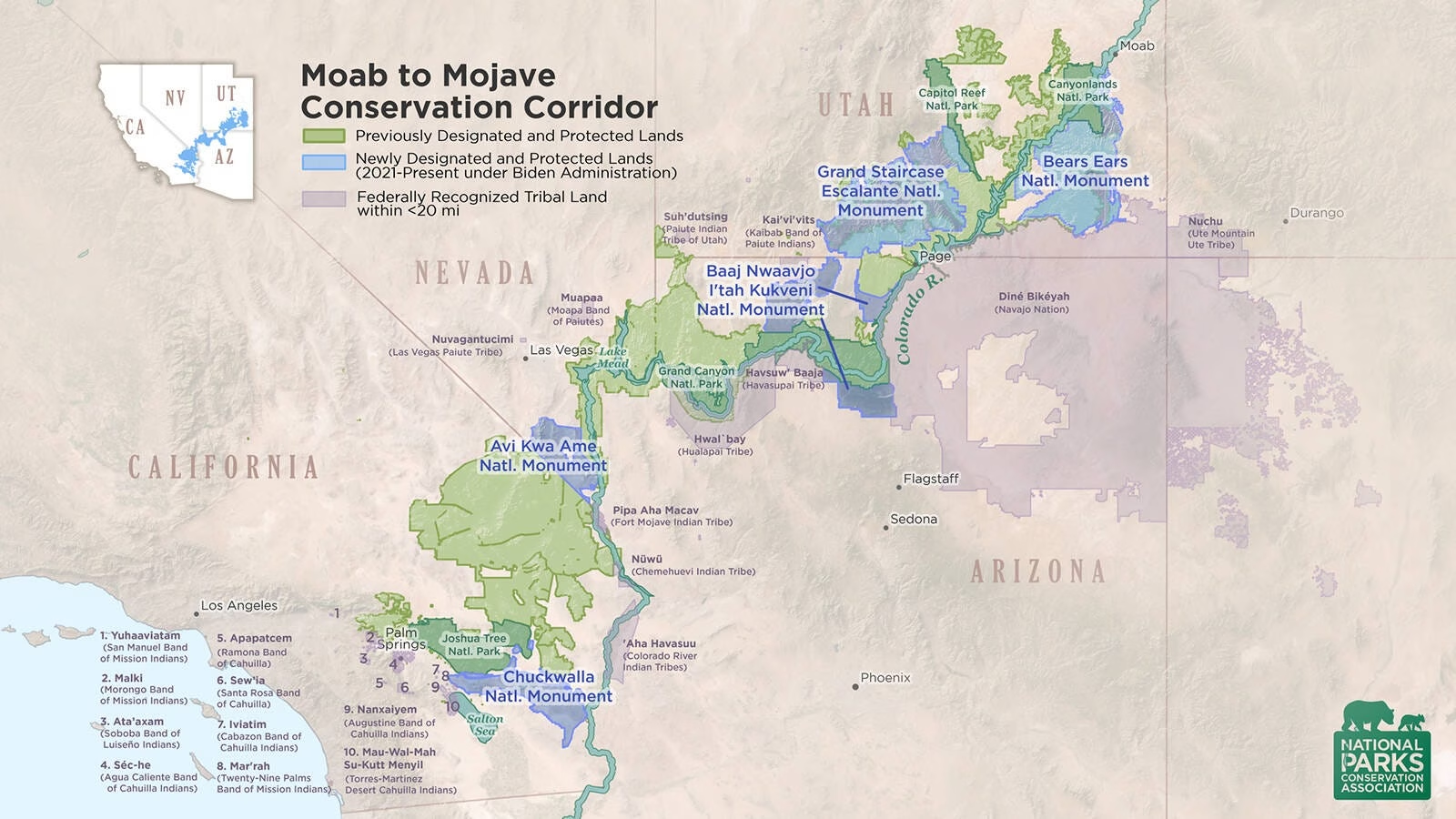

On January 7, as one of his last actions before leaving office, President Joe Biden signed an executive order establishing the Moab to Mojave Conservation Corridor (M2M), which does the same for the Southwest. A swath of protected lands covering nearly 18 million acres and stretching approximately 600 miles from Bears Ears National Monument in southeast Utah to the newly established Chuckwalla National Monument in southern California, M2M links four national parks with five national monuments and Glen Canyon National Recreation Area. According to the National Parks Conservation Association, it is the “largest corridor of protected land in the continental United States.”

(Map courtesy of National Parks Conservation Association, 2025)

The M2M corridor already includes some of the most heavily visited tourist destinations in the country, but due to rapid population growth, the Colorado River and its sub-basins are experiencing some of the heaviest demand of any natural resources in the nation. As pressures for commercial and industrial development mount across this arid landscape, the ecological integrity of the greater Colorado River landscape will be crucial to maintaining both biological integrity and human habitability. For example, in the Southwest, big game such as mule deer, pronghorn, elk, and desert bighorn sheep undertake daily and seasonal migrations, navigating urban sprawl and frequently crossing treacherous roads and highways; Riparian ecosystems harbor the region’s greatest biodiversity, and are crucial habitat for birds, fish, and rare plants. Riverscapes, therefore, especially ones as large and complex as the Colorado, demand regional outlook. By offering a framework for land managers and their partners to work strategically on creative solutions to habitat connectivity problems, M2M seeks to enhance ecological linkages between units and act as a crucial bridge to the future.

The M2M corridor will also help preserve Tribal sovereignty for the many Native American tribes that call the Colorado River home. Much as nature does not adhere to arbitrary borders, the history and stories of Native peoples weave a complex fabric that permeates ancestral territories across the entire M2M landscape. For peoples who have been repeatedly stripped of land and rights—for whom history is literally written into land itself—M2M provides additional basis for the protection of cultural heritage sites within the context of the natural landscape.

Finally, M2M seeks to promote wise commercial and industrial development, including housing, renewable energy projects, and oil & gas production. Since recreation is a major economic driver across the corridor, unobstructed viewsheds are one of its prized assets. Landscape-scale connectivity does not mean blocking all development, though, or disregarding the concerns of local communities. Rather, it seeks to bring communities into decisions over the lands that determine the shape of their lives and livelihoods, to provide tools and rationale for maximizing livability and longevity.

The goal of landscape-scale conservation is balancing competing interests for the long-term benefit of humans and the environment. Designation of National Monuments, such as Baaj-Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni and Avi Kwa Ame, both established by Biden, are one way of doing that. It’s important to note, however, that designation of the M2M corridor does not preclude existing land uses such as grazing, hunting, OHV use, or rockhounding. It remains to be seen how M2M will be implemented, but it does orient federal policy toward a broader, more inclusive view of what public lands are for, and how best to steward them. It may also help galvanize support among nonprofit partners and the general public for landscape connectivity, allowing greater cooperation on shared conservation initiatives and goals. Get out and experience this boundaryless landscape for yourself!

Kevin Berend, Conservation Programs Manager

[Image credit: Tyler Casey via Unsplash]