Often, we think of plants as inherently inert objects, composing the static background of the environment and incapable of movement, interaction, or influence. However, for one plant this notion could not be further from the truth. In fact, it may just have explored more of the American Southwest than you!

The four corners potato, Solanum jamesii, is a perennial, tuber-producing plant of the infamously toxic nightshade family (Solanaceae) closely related to the modern potato. The tuber of the plant is highly productive, winter-withstanding, nutritious and harmless when thoroughly cooked to destroy toxins. Native to the Mogollon region of central Arizona and New Mexico, the plant’s range extends in isolated populations across the Four Corners into Colorado, here in southwestern Utah, and as far south as Texas. The plant grows at elevations of 4,700 to 8,500 feet in moist sandy soils and can be identified by its white, star-shaped flowers and bulbously protruding yellow stamens. Despite millennia of agricultural use in and around Grand Staircase Escalante National Monument, special care must be taken to correctly identify members of the family Solanaceae and wild plants should never be foraged for consumption.

The Four Corners Potato (Solanum jamesii) [photo Native Plant Society of New Mexico]

To understand how the four corners potato arrived in the Escalante, we must first understand its reproductive biology. S. jamesii is an obligate outcrosser, meaning it requires genetic material from another individual to sexually reproduce and cannot self-fertilize. However, the plant requires very specific genetic and environmental conditions for this sexual reproduction to occur, and more often propagates close-range through its tuber—the enlarged, underground rhizome structure commonly known as a potato. When outcrossing does occur, the seeds bear the signature toxin solanine which prevents dispersal by birds or mammals. So, how did this homebody spud find its way north across state lines?

A team of researchers led by Bruce Pavlik, botanist and Conservation Director for Red Butte Gardens in Salt Lake City, were intrigued by the genetic origins of these isolated potato populations, separated from their native range by hundreds of miles of bare rock and dry sands. In 2023 they published a paper in the American Journal of Botany, describing the genetic distribution of S. jamesii based on samples obtained from archaeological and non-archaeological sites across the Southwest United States. Analyzing 25 populations across five states, a litany of genetic tests revealed the hitchhiking penchant of these potatoes.

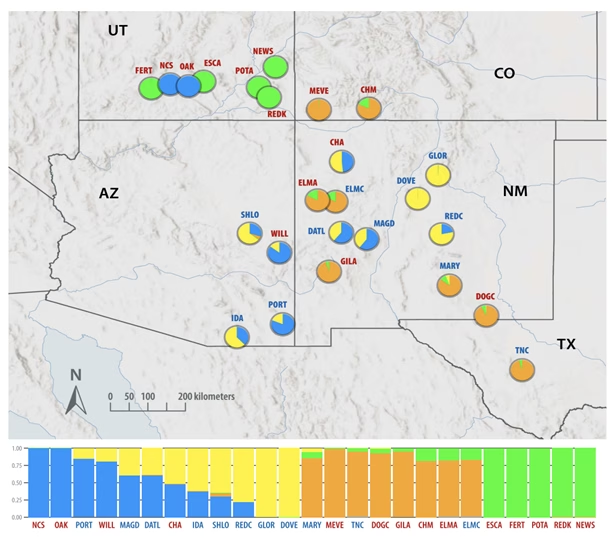

Populations of potatoes sampled from archaeological sites were significantly less genetically diverse than those sampled from non-archaeological sites, especially from the native Mogollon range. These results are consistent with the founder effect described in evolutionary biology—the phenomenon where a small subset of a genetically diverse population establishes an independent population and suffers a resulting decrease in genetic diversity. In the context of S. jamesii, this relative lack of genetic diversity at archaeological sites indicates that humans selected a relatively small sample of tubers from an ancestral population in the Mogollon region and dispersed them across the Four Corners as they established settlements. Since only a small and unrepresentative sample of the original population’s genetic pool were brought to establish the genetic makeup of the new isolated populations and the potato plants rarely outcross, the frequency of genes present in these isolated potato populations skew heavily towards those of the founders.

One of the most intriguing insights of the paper comes from a cluster of archaeological sites just outside the Monument near the present-day town of Escalante. The researchers sampled four small populations of potatoes from the Escalante valley and found them consisting of two genetically distinct groups, despite their proximity. Two such populations were closely related and marked by a preference for growth under the shade of Gambel oaks. The other two were found to be genetically closer to populations sampled from Bears Ears National Monument and not their oak-loving neighbors. Additionally, both populations groups were quite genetically similar, indicating a close clonal relationship within the two groups and confirming the lack of reproduction between them.

Since the two population groups are so geographically proximate yet so genetically distinct, they must have been introduced to the valley by humans on at least two occasions, each time drawing from a different genetic subset of the ancestral population. Wide geographic distribution of very close relatives across the area of study also supports the same hypothesis: individuals from successive founder events radiated across the Four Corners via human transport and establishment. As a general trend, genetic relatedness bore no relation to geographic proximity as explained by the natural dispersal patterns of S. jamesii (see Figure below).

GENETIC COMPOSITION OF S. JAMESII POPULATIONS (adapted from Pavlik et al. 2023). Locations of sampled S. jamesii populations as displayed by their genetic composition. Site codes labeled in red indicate archeological sites whereas those labeled in blue indicate non-archaeological sites. The circle and bar charts associated with each site indicate the proportion of the population originating from four distinct source populations, colored in blue, yellow, orange, and green. Notice the genetically heterogenous (diverse) composition of populations from the Mogollon compared to the homogenously composed satellite populations. Notice also the two source population groups composing the four clonal populations sampled in the Escalante Valley, indicated by a red box.

This study decodes the opening lines in an ongoing chapter of human history in the Escalante as people began not merely to subsist on the land but tailor it to their liking, permanently altering the biological signature of the region. The significance of human-plant relationships is rarely one-sided. Just as humans facilitated the expansion of S. jamesii through the Four Corners, so did this important staple crop facilitate the establishment of Escalante’s first peoples.

– Jack Behrens, GSEP intern

References:

Pavlik BM, Del Rio A, Bamberg J, Louderback LA. Evidence for human-caused founder effect in populations of Solanum jamesii at archaeological sites: II. Genetic sequencing establishes ancient transport across the Southwest USA. Am J Bot. 2024 Jul;111(7):e16365.

Miller GO. “Solanum Jamesii.” Wildflowers of New Mexico, Native Plant Society of New Mexico, www.npsnm.org/wildflowersnm/Solanum_jamesii.html.